Lesther Martin, a World Language Academy teacher originally from Guatemala, teaches his fourth-graders social studies. Photo by Dan Carsen.

As public schools become more linguistically diverse, some see bilingual or “dual-language” programs as a way to improve education for all – English speakers too. Yesterday we checked out an innovative dual-language school in a low-income Georgia neighborhood just outside Atlanta. Today we’ll visit a program 50 miles to the northeast, where staff combine the approach from that first school with resources from a more solidly middle-class community. That promising mix has become a model.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

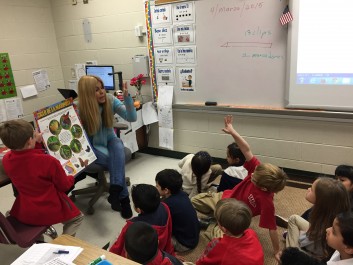

World Language Academy is a place where the middle school has an indoor multi-floor “learning commons” some colleges would envy, and the program’s

foundation helps buy duplicate materials written in multiple tongues. It’s a place where first-graders of all backgrounds talk about butterflies in Spanish, and where white middle-schoolers speak Spanish – or Mandarin – in the halls. The largest proportion of the student body is Latino, then white, then smaller numbers of blacks and Asians. And students aren’t the only ones connecting across cultures.

“I feel like I’ve been a bubble my whole life. And coming here, I’m the minority,” says Lane Sharrett, a fourth-grade teacher who is white.

She grew up nearby in Flowery Branch, Georgia, and unlike many of her colleagues, who hail from more than a dozen mainly Spanish-speaking countries,

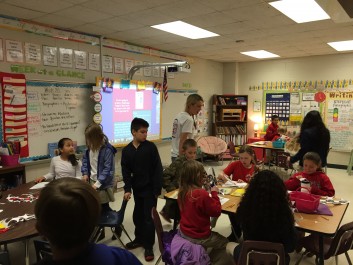

WLA fourth-grade teacher Lane Sharrett gets ready to start a history lesson. She’s one of the few teachers in the building who’s from the United States and teaches in English.” Photo by Dan Carsen.

she teaches in English. She admits that in her youth, she and everyone she knew assumed “any Latino was Mexican.” She’s learned a lot about cultures and about bilingual education since then. Her students’ (and the whole schools’) test scores are very good, even though the tests are in a language in which her kids are taught just half the time:

“My students are on third-grade reading levels here, but they’ve only really gotten half of their day in [English], and they’re still meeting – actually more or less exceeding – where they’re supposed to be,” she says.

Those kinds of results, and the bilingual or dual language approach in general, demand tremendous teamwork at WLA’s preschool, elementary, and middle-school campuses.

“I have to trust that the Spanish teacher is teaching the standards that need to be taught for my students, and vice-versa,” Sharrett explains. “There’s a lot of collaboration to make sure that we’re hitting all those standards. You have two totally different teachers, two totally different cultures coming together.”

But when kids who don’t speak English come together in traditional English immersion classrooms – the most common approach across the South and the U.S. –the message many get is that their language is less valued, and educators say they can internalize that. WLA teacher and bilingual education advocate Jason Mizell is one of them:

Estudiantes y mariposas: First-grade teacher Vivianne Delgado and her students are learning about butterflies, but they’re also learning to describe and associate in Spanish.” Photo by Dan Carsen.

“If you make a kid feel valued, they will do anything for you. But the moment you make them feel you have something against them, they shut down. In a dual-language school, that’s one hurdle you don’t have to go over. Kids know that they’re valued, their families are valued.”

And people from the dominant language group can benefit too, people like Skyler, who’s in eighth grade and loves writing.

“It’ll give me a lot more job opportunities – I’ll be able to translate for some companies,” he says.

But after so many reports about how being bilingual boosts brain development, I’m curious about something else. I ask the budding language-hopper if he thinks in Spanish. He does:

“Sometimes it’ll just get into me, and I’ll just start thinkin’ in Spanish, and I don’t realize it. And then I’ll go back to English and I won’t even notice.”

WLA elementary parent Harmon Tison sees that kind of development in his fourth-grader and second-grader. They helped the family traveling in rural Costa

Skyler is an eighth-grader who hopes his knowledge of Spanish will help him land better jobs in the future. He also dreams in Spanish. Photo by Dan Carsen.

Rica, including haggling in open-air markets where prices are “negotiable.” But their learning core subjects in Spanish comes with some frustrations: Tison can’t help his kids with their homework, which he says has helped him understand what language-minority parents face all the time.

“A lot of times, human nature is selfish,” he says. “You don’t realize the decisions you make, the impact they have on other people, not only in your community, or in your state, or maybe in your country, or maybe even the world. And we want ‘em to be able to think outside the box and be able to realize we’re all in this together.”

Most language-minority students don’t have access to anything like this well-funded and well-run Georgia school. And even the best possible dual-language program wouldn’t fix everything many of these kids face: “triple-segregation” by ethnicity, poverty, and language. But teaching them in the language they know at a critical period in their lives is pushing some over those hurdles, and widening the worldviews of others with fewer hurdles.

That was Part Two of our series on language-minority education in the South. (Click here for Part One.) In Part Three we cross over from Georgia into Alabama to examine the challenges, or the reasons why dual-language education isn’t more common in the South. Support for this series comes from The Equity Reporting Project: Restoring the Promise of Education, which was developed by Renaissance Journalism with funding from the Ford Foundation.