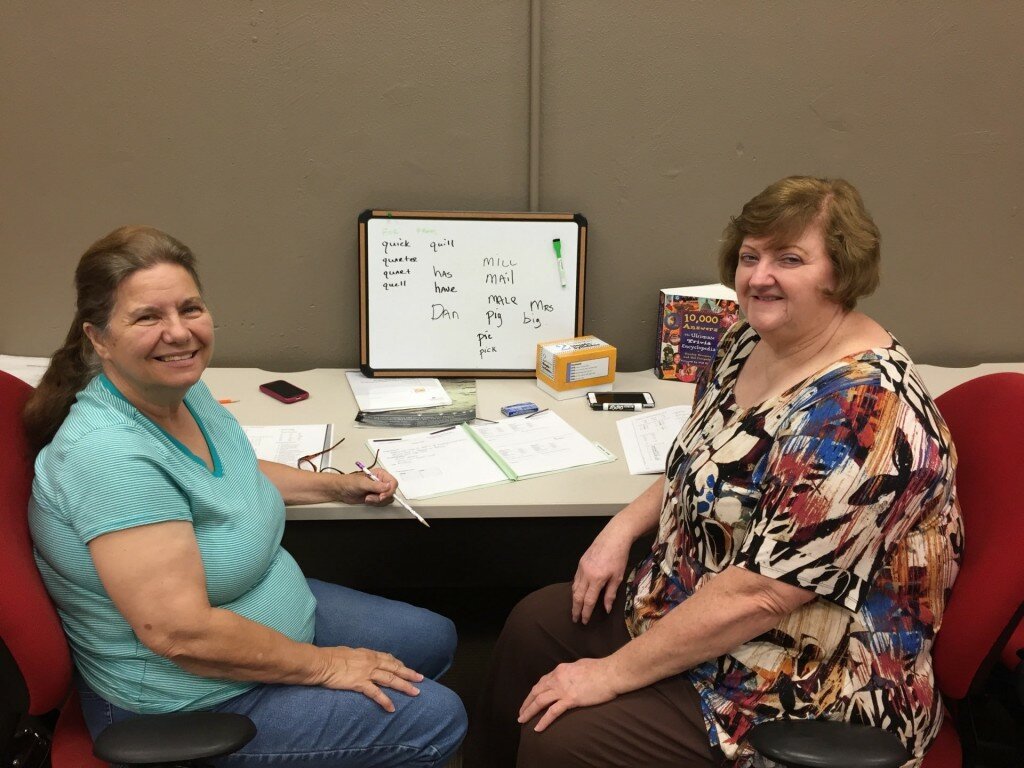

Learner Janie Morgan, left, and volunteer tutor Judy Hickman take a quick break from lessons at the Literacy Council in downtown Birmingham. Credit: Dan Carsen / WBHM

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Imagine not being able to read an email from your family. Or a job application. Or medication labels. How about a simple road sign? Adult illiteracy is a complex, stubborn problem. Based on conservative estimates, in the five-county area around Birmingham alone, there are more than 90,000 adults who have trouble reading and writing. And there are almost as many reasons as there are people.

“When I was little, my family didn’t have time for me,” says Janie Morgan, 61, of Bessemer. “So I had to try to learn as much as I could on my own. And then when I went to school there were so many kids there that they really couldn’t just help just one person.”

Essie Johnson, 59, of Birmingham adds, “My mom … she was a good mom. [But] my dad and her broke up, and she became an alcoholic. I had to take care of her and my brothers. I didn’t go to school a lot because I had to help them. I missed out.”

Fred Oliver, 86, also of Birmingham, thinks back to the late 1930s: “I was doing good in school, but when the old man died, I had to get out and work.”

Oliver, who goes by “Mr. Fred,” started working all kinds of jobs in Birmingham when he was a child. He never really learned to read, and that lasted most of his life. When the decorated Korean War veteran’s wife died two years ago, he lost someone who’d helped him with any reading and writing that came up. Now he jokes that he’s tired of relying on his children.

“My kids take care of all my business, all my stuff, but I’m getting ready to kick ‘em all out!”

But as we talk, he gets more serious.

“I’m still learning,” he says. “You’re never too old to learn. And you’re never too old to learn how to read better. And do better in your life.”

Mr. Fred and about 150 other learners are doing that through The Literacy Council of Central Alabama. The 25-year-old Birmingham-based nonprofit is a United Way agency funded by donations from foundations, corporations, and individuals. As volunteers work one-on-one with learners, In-House Programs Director Adrienne Marshall describes her motivations.

“Early on, I started realizing how enjoyable it was to read,” she says. “And how much of an escape it can be. How informative it can be. And it just hurt my heart to think that not everybody had that same access because they couldn’t grasp the words on the page and what they meant.”

That undermines not just personal enjoyment, health, and safety, but the wider economy – to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars in Alabama alone. It’s hard to get most jobs when you can’t read or write. High illiteracy rates also discourage companies from moving in and offering those jobs in the first place. So the Literacy Council brings together volunteers to work with adults who want to be better readers and writers.

One of those volunteers is James Mersmann, who’s quickly pointing to words for Mr. Fred to read. He’s moving his pencil so fast I ask Mersmann if he’s trying to trick Mr. Fred. Mersmann laughs and says, “Well I’m going fast and changing the pace, because if I didn’t have a lot of them in there he’d just memorize the location of them.” Mr. Fred compliments Mersmann’s technique, so I ask Mr. Fred whether liking and feeling comfortable with his tutor boosts the learning process.

“Oh yeah,” he says. “I’m learning how to read, and what words mean. I’m trying to get what James got!”

In between lessons, Mersmann and Mr. Fred trash-talk like old buddies about who can run faster. Literacy Council staff say that vital personal bond often evolves naturally because you have people who’ve acknowledged they need help working side-by-side with people who just want to help — there’s no pay involved here.

Janie Morgan is so thankful she wants to teach other adults to read once she masters it. Her tutor Judy Hickman says, “Janie is just so positive and wanting to learn. All of the learners here are really inspiring because it takes a lot of courage to step out and admit something that you can’t do. And to come in with that desire to learn, at whatever level they need to start, as well as the commitment to keep coming and not get discouraged, to look for the little victories … there are a lot of victories here.”

“I’m really learning a lot,” agrees Morgan, “because these people up here will help you. And they will encourage you. And they will love you. And love is very important.”

The 61-year-old says no one should be embarrassed or worried about what people “who don’t know your story” think.

“I mean, you could be 90 years old, and if you don’t know how to read, come on in.”

He isn’t quite 90, but 86-year-old Mr. Fred agrees.

“I love this school. If they close this school, I don’t know what I’d do … I love everybody here.”

Hear more from “Mr. Fred,” pictured below, in Part Two of this report. This story was originally published on November 1, 2016.

“Mr. Fred” Oliver, 86, after a morning of improving his reading and writing at the Literacy Council of Central Alabama. Credit: Dan Carsen / WBHM.

Pingback:Southern Education Desk – A Conversation with “Mr. Fred,” 86-Year-Old Learning to Read